The Pluralistic Future of Spirituality

Challenging Staid Dogma and Religious Exceptionalism in the 21st Century

Rational Spirituality humbly engages with Supreme Truth, a metaphor for God, through the lenses of quantum physics, wisdom and sacred literature including the Bible and Koran and through personal intuition, which is intrinsically interlaced with one's higher consciousness. Higher consciousness, which is non-local consciousness,1 is itself synonymous with what Christians refer to as the Holy Spirit. In different cultures, this universal life force or spirit is venerated using other names, such as Prana, Qi or Chi and Pneuma, et al.

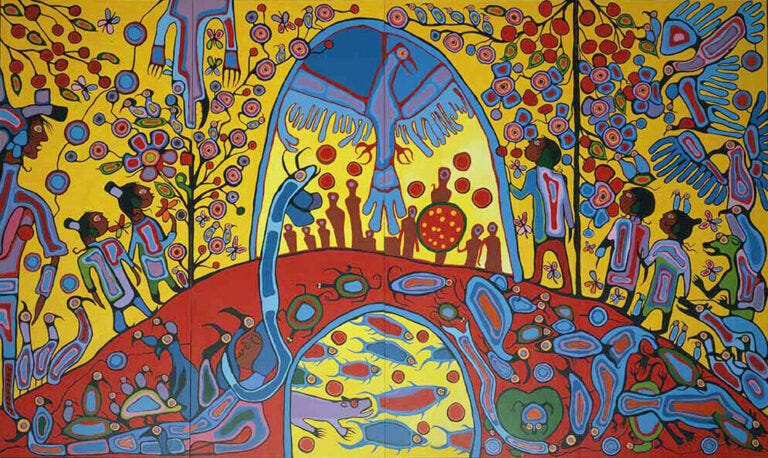

In a world increasingly fragmented by ideology, dogma and religious rivalry, the clarion call for pluralism has never been more urgent. Pluralism, at its core, embraces the vagaries of human religious and spiritual experience, encouraging us to transcend the limitations of sectarianism.

However men try to reach me, so do I welcome them, for the path men take from every side is mine.

Bhagavad Gita 4:11

The monolithic approach, which often claims the exclusivity of one path to God, fails to honor the diverse ways in which the Divine can be understood and experienced. All religions encourage us to move beyond the limitations of sectarianism, which present stumbling blocks to holiness.

John Hick, a towering figure in the philosophy of religion, provides a convincing argument against such exclusivity. He posits the idea of an "Ultimate Reality" that transcends human understanding and religious categorization. For Hick, the Divine can manifest in an infinite number of forms, often shaped by the cultural, historical and personal contexts in which people find themselves. This goes beyond mere religious tolerance, making room for a spiritually enriching mosaic where God's grace is universally accessible.

This view aligns with biblical teachings often overlooked in mainstream Christian doctrine. The Apostle Paul, for example, states, "God does not show favoritism but accepts from every nation the one who fears him and does what is right" (Acts 10:34-35). Paul’s statement was revolutionary for his time and remains so today; it expands the notion of divine grace beyond the boundaries of any particular faith community.

Karen Armstrong, a renowned religious scholar, reminds us that the Bible itself is neither history nor biography. Her teachings echo the ancient tradition of viewing scripture as a living document, one that offers multiple layers of truth that go beyond the literal to the symbolic and mystical. When we cling solely to a literal interpretation, we risk missing out on the depth and breadth of wisdom these ancient texts offer.

John's Gospel, often cited to justify religious exclusivity, should be understood for what it is: theology, not a verbatim account of Jesus' teachings. Unlike the Synoptic Gospels - Matthew, Mark, and Luke - which derive from common sources and emphasize Jesus' teachings and parables, John focuses instead on the theological implications of Jesus as the Christ. It eschews the parables that characterize the Synoptics and has a high Christology that reflects a different community and set of concerns.

Then there are theologians like John Shelby Spong and Paul Tillich who have challenged conventional Christian viewpoints. Spong deconstructs literalist Christianity, urging a more inclusive understanding of the Divine, while Tillich speaks of God as the "Ground of Being," a concept that transcends any specific religious narrative and is akin to Hick’s Ultimate Reality.

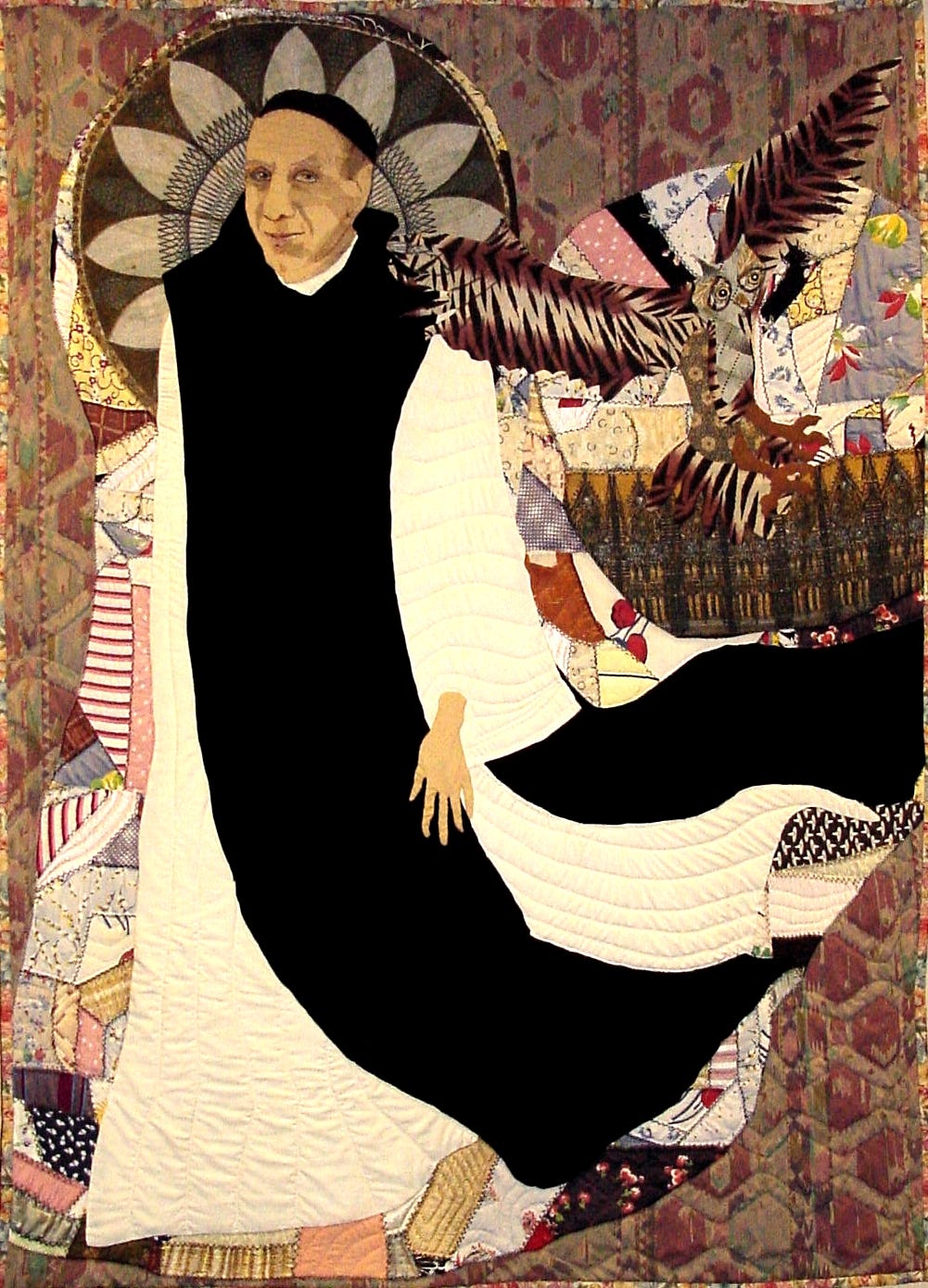

Both Thomas Merton, a Trappist monk, author and spiritual giant, and Matthew Fox, a theologian, author and Episcopal priest, have extended the boundaries of Christian thought. Merton's exploration of Eastern religions and Fox's creation-centered spirituality invite us to experience the Divine in myriad ways, reaffirming that God's grace is not the exclusive domain of any one religious tradition. Both discuss the interconnectivity of all beings, a theme that echoes through various religious and spiritual traditions.

Following this train of thought, Meister Eckhart, a 14th century Dominican monk, whose work was studied extensively by Merton, offers a crucial dimension to our understanding of universal love and God's grace. In his sermon on Love,2 Eckhart also speaks to the interconnectedness of all beings. Drawing inspiration from John 14, where Jesus advises us to "love one another," Eckhart extends this notion of love to a cosmic level, advocating for a love that envelopes all creatures and transcends religious labels.

Eckhart’s perspective acts as a counterpoint to more exclusionary interpretations of religious texts, such as the oft-cited verse from John's Gospel: "No one comes to the Father except through me." As Karen Armstrong keenly observes, it's highly unlikely that a first-century Jew like Jesus would make an exclusivist claim. Armstrong’s point helps demystify the intent behind such scriptural passages, allowing us to appreciate them as products of specific cultural and theological contexts rather than as universal dictates.

Who Wrote the Bible?

In understanding the New Testament, particularly the Synoptic Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke, it's essential to know about the 'Q' document, or 'Quelle,'3 which means 'source' in German. This theoretical collection of the sayings of Jesus is thought to have been used by the authors of these three Gospels and provides a significant portion of their content.

Additionally, it's worth noting the term ipsissima verba, which refers to the very words of Jesus. Biblical scholars believe we have only about five or six instances where we can confidently assert that these are the exact words spoken by Jesus himself. This reality emphasizes the interpretive lens through which the Bible was written and compiled, suggesting that the spiritual truths it contains should be understood in more universally applicable terms.

Many biblical scholars agree that few of the quotes John puts in Jesus' mouth were actually uttered by Jesus. This is why John's Gospel is set apart from the synoptic Gospels and treated as theology. It is also written in a more philosophical and reflective style, emphasizing the divinity of Jesus much more explicitly than do the Synoptic Gospels.

In the grand scheme of the cosmos, it's not just humans who are participants in this Divine Love. The Bible, in multiple instances, refers to "all creatures," not merely humans. If the universe is ensouled, as panpsychism4 suggests, this surely extends to the animal kingdom. Our beloved pets, members of our earthly families, will also be with us in the Afterlife, however we conceive it to be. This isn't just a comforting thought; it's a natural extension of the belief in a universe imbued with Divine Love and Intelligence.

In this age of ideological polarization, the need for religious and spiritual pluralism is critical. The notion that God's grace extends universally, irrespective of religious or cultural background, is not merely a theological stance; it is a vital perspective that fosters global unity and mutual respect.

My understanding of religion was transformed nearly 30 years ago by the great Muslim scholar and mystic Ibn al-Arabi (1165-1240). Sadly, he is little known in the West. A truly religious person, he insisted in “Fusus al-Hikam,” was equally at home in a synagogue, temple, church or mosque, since no faith has the monopoly of truth.

~ Karen Armstrong

Cultivation of a Rational Spirituality is not simply an intellectual exercise, but rather is a crucial aspect of our collective survival and growth. Through the arguments laid out in this piece - ranging from John Hick's concept of 'Ultimate Reality' to Karen Armstrong's contextual reading of religious texts - we propose a spirituality that respects diverse paths to the Divine, embraces the interconnectedness of all beings and seeks to evolve our collective consciousness.

In contrast to dogmatic religious frameworks, which often serve as breeding grounds for sectarian nitpicking, those mystical and mythological elements present in every spiritual tradition lead to a more universal truth: that there are as many paths to the Divine as there are individuals to walk them.5

Our rational approach to spirituality aligns with evolution toward a higher form of consciousness, or Superconsciousness,6 as envisioned in Aquarian Age expectations. Superconsciousness transcends dogmatic rigidity and presents a blueprint for a more harmonious, compassionate and enlightened future.

May we all become Watchers - steadfast stewards of a new, more inclusive spirituality that honors the Divine in all its manifold expressions.

Non-local consciousness is the scientific theory that consciousness is not limited to individual brains or bodies but is instead a field of energy that is interconnected and shared by all beings. (Source)

In the philosophy of mind, panpsychism is the view that the mind or a mindlike aspect is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of reality. (Wiki)

A History of God (book), by Karen Armstrong, 1993. [Highly recommended!]