“Two Romes have fallen, the third stands, and there will be no fourth.”1

Nestled within the voluminous pages of Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Brothers Karamazov lies a masterful story within a story. Set in the late 15th or early 16th century in Seville, Spain, it narrates Jesus' return to Earth. This time, our Lord clashes not with a Roman governor, but with an aged and calculating Cardinal of the Roman Church—the Grand Inquisitor — who orders Jesus’ immediate arrest.

Imprisoned, Jesus silently endures the Grand Inquisitor’s chastisement. The Inquisitor questions the wisdom of Jesus' return, insisting that his miracles cause unrest and that people prefer the certainty and sustenance provided by the Church over the challenges of freedom and individual responsibility. He argues that the Church has supplanted Jesus in guiding the people, offering structure in place of the burdens that come with liberty.

The climax of the tale is marked by Jesus's response — a compassionate kiss, prompting the Grand Inquisitor to release him with a stern warning never to return: “Go, and come no more . . . come not at all, never, never!”

This encounter serves as a critique of institutional power and its authoritarian tendencies, portraying the Inquisitor's preference for authority over Jesus as a cautionary tale against centralized power. Dostoevsky believed that the Tsar and the people should form a unity. He wrote, “For the people, the tsar is not an external power, not the power of some conqueror...but a power of all the people, an all-unifying power the people themselves desired."

This narrative layer reveals subtle insights into human nature, freedom, and the tension between spiritual truth and worldly power. The Grand Inquisitor, a metaphor for a church more concerned with temporal power than spiritual guidance, reflects a shift from serving the ecclesiastical community to cherishing control and opulence.

This transformation mirrors a larger one within Western Civilization, which is itself grappling with existential crises and ideological challenges. A Marxist-leaning cabal of financiers and technocrats is seen as orchestrating a transformation toward an irreligious, autocratic global order diametrically opposed to traditional Western values.

Faced with the evil and brokenness of the world, leftism responds not by turning toward God, nor by first seeking to tame the evil of one’s own heart, but by seeking power. Call it critical theory, anticolonialism, or just old-fashioned Marxism — the promise of leftism is that power, properly redistributed from the oppressors and to the oppressed, can be used to remake the world.2

Leftism, viewed here as a distortion of religion, seeks to address world evils not through spirituality but through power and wealth redistribution, aiming to reshape the world. This perspective suggests that on the international stage, the Cabal’s vision of a new global order is increasingly challenged by a non-Anglocentric rival, signaling a shift towards a multipolar or multinodal world order. The term “nodal” implies communication and cooperation among various centers of power.

This emerging force challenges established paradigms, hinting at a multinodal Novus Ordo Seclorum—a ‘New Order of the Ages’— that transcends the traditional Western-centric perspective.

Holy Rus: Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia

The dual concepts of ‘Holy Rus’ and Moscow as the ‘Third Rome’ are deeply ingrained in Russia's spiritual psyche and historical narrative. These intertwining notions serve as the metaphysical bedrock, blending Russian Orthodoxy with a profound sense of national identity.

This evolving national identity is foundational to a vision crucial for understanding Russia's perception of itself and its positioning within the muddled web of global geopolitics.

The opening quote, “Two Romes have fallen, the third stands, and there will be no fourth,” refers to Rome, Constantinople and Moscow as successive standard bearers of Christianity. It is attributed to a Russian monk in 1510.

This vision of Russia as a Third Rome evokes an introspective journey, contrasting the archetypal mindsets of the Western and Eastern worlds. This voyage reveals a striking architectural dichotomy: the soaring Gothic cathedrals of the West, with their sky-piercing spires reaching ever upward in a relentless quest for the mystical divine, stand in contrast to the Eastern Byzantine basilicas, crowned with domes that embody the presence of the sacred here on Earth.

Gothic architecture is emblematic of the Western ‘I’— a symbol of the individual's introspective quest and subjective experiences. In contrast, the Byzantine domes reflect the Eastern ‘We’— a shared experience of the divine, interwoven with communal reality and collective spirituality.

It is the Western ‘I’ that is under attack today. Attack not by an earthly army but by a spiritual entity known as the Antichrist. I wrote about that subject here.

This essay delves into the theological underpinnings and historical evolution of ‘Holy Rus’ and the ‘Third Rome,’ examining their contemporary expressions, particularly through the lens of Russian philosopher Alexander Dugin's ideology. It further assesses the impact of these concepts on Russia's geopolitical maneuvers in Ukraine and the broader Eurasian context.

Our intent is not to romanticize Russia or serve as her apologist but rather to engage with her psyche and illuminate the metaphysical struggle in which she is deeply implicated — a metastable yet profound confrontation between civilizations.

This struggle is marked by the perception of Western Civilization as an empire in its twilight, juxtaposed against the dawning of a new Eurasianism, embodied in the concept of 'Holy Rus.' This emerging concept signifies the reawakening of an awe-inspiring ancient ethos into the modern world.

The resurgence of the Russian Orthodox Church as a central figure in shaping national identity and geopolitical strategy cannot be overstated. The Church's influence extends beyond religious practice, embedding itself into the very fabric of Russian statehood and foreign policy. This symbiosis between Church and state enhances Russia's portrayal as a protector of traditional values, countering what it perceives as the moral decay of the secular West.

‘Holy Rus’ envisions the Russian nation and its people as custodians of Orthodox Christian tenets and moral values. This concept took root when Russia embraced Christianity from Byzantium in the 10th century, inspiring a spiritual identity that has been continuously reinforced through pivotal historical milestones, including the Mongol invasions and the eventual decline of the Byzantine Empire.

Throughout the centuries, Russian Orthodoxy has endowed Mother Russia with a sense of transcendent destiny and divine mission, deeply embedding a spiritual imperative into her national consciousness. This was historical perspective informed Putin’s approach to his interview with Tucker Carlson. This perspective has not only shaped the nation's past but continues to influence both its present and future trajectories on the global stage.

The Third Rome

The notion of Moscow as the ‘Third Rome’ emerged in the wake of the fall of Constantinople in 1453. This compelling concept positions Moscow as the heir apparent to the spiritual mantle of ancient Rome and Byzantium, envisioning it as the burgeoning epicenter of global Christianity. Here, Moscow is not merely a city but a symbol — a beacon assuming the role of safeguarding and leading the true Christian faith.

This idea, deeply rooted in Byzantine intellectual tradition, was cultivated and articulated by Russian monks and theologians. They envisioned Russia as the natural successor to Byzantium's rich spiritual heritage, a conviction that has profoundly influenced Russian self-awareness. The ‘Third Rome’ doctrine permeates the Russian psyche, imbuing it not only with a sense of destiny, but as promising a pivotal role in the religious narrative of the world.

In contemporary times, Alexander Dugin, a figure shrouded in controversy for his philosophical and political theories,3 has reinvigorated these ancient concepts, seamlessly melding them with his vision of Eurasianism. Often likened to a ‘modern-day Rasputin’ due to his considerable influence in Russian politics, Dugin casts Russia in the role of the katechon — a term drawn from Christian eschatology that refers to a restraining force holding back the Antichrist.

Dugin's brand of Eurasianism champions the emergence of a Russocentric geopolitical sphere, directly challenging the ideals of Western liberalism. He positions Russia as a civilization upholding traditional values, a bastion against the tide of modern secularism. His philosophy lends an eschatological dimension to Eurasianism, spiritizing Russia's geopolitical endeavors with what he perceives as a divinely orchestrated purpose.

The Russian Orthodox Church's stance on the conflict in Eastern Ukraine illustrates the complex and sometimes fraught nexus between spiritual doctrine and geopolitical ambition. The Church's support of the conflict underscores the influence religious beliefs exert in shaping Russia’s national strategy and foreign policy, reflecting the roles of faith and power in the realm of international relations.

According to this view, after Rome, the Catholic-Orthodox schism lost the right to be considered the center of Christianity. That right was transferred to Constantinople. After Constantinople fell to the Ottoman Turks, as Philotheus of Pskov wrote in 1511 — Moscow became the ‘Third Rome.’ In order to understand the main spiritual root of contemporary Russian aggression in the light of the idea of the ‘Holy Rus,’ it is necessary to understand that the Russian political [and religious] leadership does not see this war as a conflict with Ukraine, but with the entire West, symbolized by NATO.4

Alongside Vladimir Putin and Alexander Dugin, Ivan Ilyin, a Russian philosopher, writer, and political theorist, has significantly influenced the development of the ‘Holy Rus’ ideology, which views Russia as a unique spiritual and civilizational entity. His contributions are rooted in a blend of religious philosophy, nationalism, and conservative thought.

Ilyin’s ideas have experienced a resurgence in contemporary Russia, particularly among Russian conservatives and nationalists. His vision of Russia as a distinct spiritual and moral beacon has shaped modern interpretations of the ‘Holy Rus’ ideology.

Understanding Russia's resurgence requires acknowledging its historical relationship with the West, particularly its experiences of being both a partner and adversary. From the Napoleonic Wars to the Cold War, Russia's identity has been shaped by its interactions with Western powers. This historical context provides insight into the current geopolitical landscape, where Russia views itself as both a defender of its sovereignty and a guardian of a distinct civilizational path.

The conflation of ‘Holy Rus,’ the concept of the ‘Third Rome,’ and contemporary Eurasianism reflects Russia's ongoing struggle to reconcile this rich spiritual heritage with its geopolitical ambitions. This highlights the significant impact of religious and historical consciousness on current global affairs.

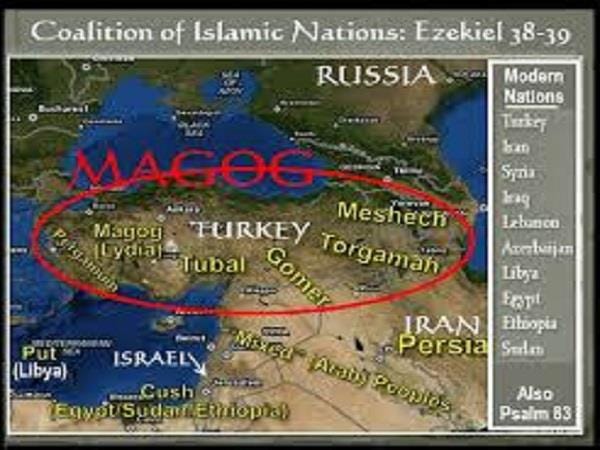

In referencing contemporary world events, this essay extends its scope beyond the Ukrainian-Russian conflict to encompass broader geopolitical tensions, including the Israeli-Hamas conflict and the eschatologically significant Gog-Magog War prophesied by Ezekiel. Magog is now believed to refer to Turkey. At one time, not so long ago, scholars incorrectly believed Magog referred to Russia.

Today, there is near unanimous agreement among scholarly Bible commentators and Bible atlases that Magog, Meshech and Tubal once were located in what is today’s modern Turkey.

This essay’s broad-based perspective challenges traditional myopic Western perceptions and acknowledges, indeed welcomes, the potential emergence of a Eurasian Civilization, led by Moscow, from the ash heap of current global turmoil. It underscores Russia's historical familiarity with empire and suggests the possible return to such a status. Such an eventuality would significantly alter the current geopolitical landscape, offering a less commonly considered and reasonable version of a New World Order.

This scenario envisions a transformative shift, with Russia and the Russian Orthodox Church reasserting themselves as a dominant geopolitical force. In contrast to the secular and often materialistic worldview that dominates Western policymaking, Russia's approach is deeply inspired with spiritual and metaphysical considerations.

This divergence in worldview complicates diplomatic efforts and necessitates a more sophisticated understanding of Russia's motives. Western policymakers must recognize that actions perceived as pragmatic or strategic in the West may be driven by spiritual or eschatological imperatives in Russia.

Such a development would not only reshape the contours of international relations but also challenge the prevailing Western-centric model of secular global politics. It implies a resurgence of Russian influence extending beyond its immediate borders into a more expansive Eurasian domain.

Without a nuanced understanding of Russia's spiritual and historical motivations, there is a significant risk of misinterpreting its actions on the global stage. Such misinterpretations could lead to policy decisions that exacerbate tensions rather than mitigate them. Acknowledging the possibility of metaphysical and eschatological motivations allows for a more comprehensive analysis, reducing the likelihood of strategic errors.

Russia’s re-emergence as a formidable Christian empire, if realized, would mark a stark departure from the post-Cold War era, where Western hegemony has largely gone uncontested. Some correctly observe that demise of the West is sine qua non for a new Multipolar World Order.

Among Western foreign policy analysts, a deeper understanding of Russia's historical, cultural, and spiritually inspired motivations is imperative. Western policymakers and strategists would benefit from a more nuanced and foresighted approach, recognizing the potential implications of a resurgent Russia within a multinodal world order.

Although traditionally dismissed by Western foreign policy experts, theological and eschatological factors should be included in their calculus. This inclusion would compel policy specialists to broaden their strategic horizons, considering a range of outcomes that diverge from conventional expectations. By recognizing metaphysical influences, they can better prepare for — and possibly influence — a future where the balance of power shifts in dramatic and unexpected ways.

Russia's vision of a multinodal world order is not merely a geopolitical strategy but a civilizational mission. This vision seeks to dismantle the unipolar world dominated by Western liberalism and replace it with a system where multiple civilizations and civilization-states, each with its own values and principles, coexist and interact on a more equal footing.

For Russia, this is not about power but about preserving a way of life that it sees as under threat from globalist ideologies, most notably the Anglo-Zionist Empire and the Roman Catholic Church.5

Filofei (Philotheus) a 16th century Russian monk and author of Moscow - the Third Rome

Alexander Dugin: “This is not a war with Ukraine. It is a confrontation with globalism as an integral planetary phenomenon. It is a confrontation on all levels - geopolitical and ideological. Russia rejects everything in globalism - unipolarity, Atlantism, on the one hand, and liberalism, anti-tradition, technocracy, Great Reset in one word, on the other. It is clear that all European leaders are part of the Atlanticist liberal elite.

“And we are at war with exactly that. Hence their legitimate reaction. Russia is now being excluded from the globalist networks. It no longer has a choice: either build its world or disappear. Russia has set a course to build its world, its civilization. And now the first step is being taken. But sovereign in the face of globalism can only be a large space, a continent-state, a civilization-state. No country can withstand complete disconnection for a long time.

“Russia is now creating a field of global resistance. Its victory would be a victory for all alternative forces, both right-wing and left-wing, and for all peoples. We are, as always, starting the most difficult and dangerous processes.

“But when we win, everyone takes advantage of them. That is the way it is meant to be. We are now creating the preconditions for real multipolarity. And those who are ready to kill us now will be the first to take advantage of our feat tomorrow. I almost always write things that later come true. This will also come true.”

Stand Up To Anglo-Zionist Fascism (article)

See also this excellent video interview with Alexander Dugin:

Sinners always inevitably create hell on earth - the wages of sin are quite literally death. A "culture" of death now patterns and controls every aspect of human culture - the death-saturated values of Pentagon based military-industrial-"entertainment"/propaganda complex now controls the destiny of life on Earth (both human and non-human).

Does the all pervasive Indivisible Living Divine Reality have a will?

The Indivisible Living Divine Reality pervades every minute fraction and the paradoxical slices and dimensions of space-time.

Who chooses such a person or persons to serve and on what basis?

Being merely ideas about the nature of Reality all religious and theological ideas reduce The Living Divine Reality to the mortal human scale only. They are thus used to justify all of the inevitable horrors created by institutional religionists.

Do you by any chance know that the director of the Federalist Society is a member of Opus Dei and that First Things is closely associated with Opus Dei too. First Things also openly pretends that the Catholic church as defined by them is the only source of Truth in the world. And that all other religious world-views, including that of Protestant Christianity are in serious error and therefore, in one way or another have to be converted to the "one true way".

This site describes the in-and-outs of the totalizing way promoted by Opus Dei

http://www.odan.org

Various Islamic apologists also erroneously claim that Islam is the only True and final "religion". Islam being the supposed "final" revelation.

There is of course no such thing as a holy country, or empire.

Jesus gave an explicit criticism of such via his very angry criticism of both the ecclesiastical and political establishments of his time and place.

Only individuals one-at-a-time can be in any sense holy. Such holiness has been manifested all over the world throughout human history, in the case of Illuminated Saints, Yogis, Mystics and Sages.

Speaking of reshaping the world, especially in the case of America that is exactly what this outfit intends to do if it gains the necessary political power to do so. It has a very detailed manifesto of what it intends to do. If re-elected Donald Trump would empower this project.

http://www.project2025.org

It is funded by at least 72 deep-pockets right-wing think tanks (etc). Most/all of which are closely associated with right wing back-to-the-past Christian true-believers. And very much associated with both the money-lenders of our time and place, and the ecclesiastical establishment too as promoted by such outfits as First Things, and the Federalist Society too.

I