When everything is politicized, people retreat into mental mountaintops — dreams of the past and fantasies of the future.

Victor Davis Hanson

Happy New Year! Let’s kick it off with a short story from the Bible.

We begin in the Garden of Eden, where God pronounces eternal enmity between 'the serpent and its seed and the woman and her seed,' the latter symbolizing the human race. This 'eternal enmity' of the serpent signifies not only the pervasive presence of existential evil in the world, but also the immediate conflict between Eve's sons, Cain and Abel. We shall revisit their story directly.

Another prefiguration merits attention. In a test of faith, God commands Abraham to take his beloved son, Isaac, to the land of Moriah and offer him as a burnt offering on a designated mountain. As they ascend, Isaac inquires about the lamb for the offering. Abraham, with steadfast belief, responds that God Himself will provide the lamb. With Isaac bearing the wood for the offering on his back, they continue their journey up the mountain.

This event is a harbinger of the crucifixion of Christ. Bible stories often introduce archetypes as well as relate historical accounts. In this vein, the archetypal feminine, represented by 'the woman' in Eden, is symbolized universally by the moon and personified in Christianity by Mary, the mother of Jesus.

After a millennia or so, our narrative resumes at a tent in Hebron, in the land of Canaan, sometime around 2000 B.C. Abraham and his wife, Sarah, receive an evening visit from three figures — God and two angels. God reveals to Abraham that his descendants will inherit the land of Canaan, the 'Promised Land.' At that time, both Abraham and Sarah were well advanced in age. Hearing God's promise of progeny, Sarah's reaction is a disbelieving laugh.

In Hebrew, 'laughter' is rendered as 'Isaac,' the name Abraham gives to his first legitimate son. Previously, Abraham had fathered Ishmael, an illegitimate child by Sarah's maidservant, Hagar the Egyptian. Sarah, believing herself barren, had acquiesced to this arrangement.

As for Ishmael, I [God] have heard you [Abraham], and I will surely bless him; I will make him fruitful and multiply him greatly. He will become the father of twelve rulers, and I will make him into a great nation. But my covenant I will establish with Isaac, whom Sarah will bear to you by this time next year.

Genesis 17:20-21.

God promises Abraham that he will bless Ishmael, making him fruitful and greatly multiplying his descendants. This blessing includes the emergence of 'twelve rulers,' traditionally interpreted in Jewish and Christian traditions as twelve tribal leaders descending from Ishmael.

Some scholars, myself included, also see this as a prefiguration of the Twelve Imams in Islamic Shia theology, a subject I explore in detail here. The last of these, the 'Twelfth Imam,' embodies an Islamic messianic archetype called the Mahdi.

These twelve Islamic rulers present a parallel to the twelve tribes of Israel, who are direct descendants of Abraham through his son Isaac and grandson Jacob, later named Israel.

An additional, important point merits consideration. The Abrahamic covenant, as established during the theophany in Hebron, extends through Sarah’s lineage, specifically through Isaac and his son Jacob, rather than through Ishmael. This lineage invites a deeper exploration of 'eternal enmity' in various biblical relationships, from Eve and her descendant Sarah to the fraternal conflict between Cain and Abel, and subsequently extending to Isaac and Ishmael.

In the Biblical narrative, Cain and Abel, the first sons of Adam and Eve, present a stark contrast. Abel, a shepherd, offers a sacrifice well-received by God, while Cain's offering, as a farmer, is rejected. Driven by jealousy, Cain commits the first murder in human history by killing Abel. God's response is to curse Cain, condemning him to a life of wandering.

The phrase 'eternal enmity between Cain and Abel' symbolizes the ongoing conflict between two archetypal forces or aspects of human nature. In this context, Cain and Abel represent dualities such as aggression versus passivity, materialism versus spirituality, or human sinfulness versus innocence — extending, in extreme cases, even to the dichotomy of good versus evil.

This theological lens brings into focus the parallel between Cain and Abel and Isaac and Ishmael, raising questions about divine justice and favor, human free will, and repentance and forgiveness. The concept of 'eternal enmity' signifies the enduring impact of human actions, which continue to resonate throughout history, as evidenced in the ongoing conflicts in Israel, the ancient Land of Canaan.

Similarly, waves of spiritual warfare have reverberated through human history. The persistent conflict between the descendants of Sarah (the Jews) and those of her maidservant Hagar (the Palestinians) transcends mere geopolitical disputes, being deeply rooted in archetypes and 'eternal enmity.' At the core of radical Islam festers a deep-seated hatred, envy and jealousy towards the Jews, forming its very lifeblood and raison d'être. It is the epitome of existential evil.

So, how then is it possible to transcend this 'eternal enmity'? Regrettably, it seems it cannot be truly overcome (evil will always be with us) but must instead be mitigated through diplomatic means. Resolution can only occur once this particular occasion or stain of evil has exhausted itself and been decisively defeated.

This somber reality sets the stage for 2024, which could be viewed as the opening act of the much-anticipated End Times.

Cry ‘Havoc!’ and Let Slip the Dogs of War

I leave the task of New Year’s predictions to others, preferring instead to connect the dots within their historical contexts. After all, predictions and prophecies are essentially reinterpretations of history.

As Ecclesiastes teaches us, 'To everything there is a season.' In the coming year, I anticipate a time of breaking down rather than building up, a time of war rather than peace. This discussion suggests that the ongoing conflict between Israel and Hamas may herald the early stages of a broader conflict, biblically referred to as the Gog-Magog War.

The wisdom of the Serenity Prayer, penned by Reinhold Niebuhr, reminds us of the importance of accepting the things we cannot change. This acceptance can be nurtured by adopting the mindset Victor Davis Hanson, who describes it as the 'Monastery of the Mind.'1

While some may engage in social protests, parroting slogans like 'From the river to the sea' in a display of misguided virtue signaling, others might prefer the path of stoical withdrawal, seeking solitude and contemplation. This choice, which I myself advocate, necessitates a balancing act between action and contemplation — a form of prayer in itself.

The seemingly innocuous 'river to the sea' slogan belies its true genocidal intent: the annihilation of the state of Israel and the extermination of the Jewish people. It is a call for barbarism writ large, akin to the savagery displayed by Hamas on October 7th.

In the Monastery of the Mind, one discovers that contemplation and reflection not only afford the strength to persevere, but also serve as tools of enlightenment providing spiritual guidance to mollify the chaos and confusion.

The Monastery of the Mind is a veritable haven for those wearied by the relentless onslaught of politically spun disinformation, the endless parade of digital notifications, and the pervasive pressure to perpetually engage with the world. In its ideal form, the Monastery of the Mind becomes a sanctuary for the soul.

The practice of stoical withdrawal bolsters emotional resilience, teaching the art of equanimity in the face of both adversity and joy. This fosters a balanced approach to the vicissitudes of life.

Author Douglas Murray frequently shares an anecdote about a Jewish rabbi who acknowledges that most of his congregation are secular agnostics or atheists. A parallel narrative could as easily involve a Catholic priest. The rabbi expresses little concern over this secularism, noting that 98% of his congregation still adhere to the observance of Jewish holy days and festivals — a tradition he believes will endure.

God commanded the Jews to 'go up to Jerusalem' three times a year — at Passover, Shavuot (Pentecost), and Sukkot, also known as the Feast of Tabernacles. These pilgrimages were pivotal to Jewish religious life, particularly when the Temple in Jerusalem was still standing. They afforded opportunities for communal worship, celebration and reflection, thus reinforcing the collective identity and religious commitments of the Jewish people.

Such a commandment provides a cogent argument for the construction of a Third Temple in Jerusalem, a topic I have explored in detail here. (By the way, all of our articles focusing on the end times can easily be located by clicking the ‘End Times’ tab on our Substack homepage, which is here.)

The spiritual war we now engage in has taken a fratricidal turn, drawing into conflict the descendants — both legitimate and otherwise — of the patriarch Abraham as represented by the three monotheistic Abrahamic religions: Judaism, Judeo-Christianity, and Islam. Herein lies a struggle marked by an eternal envy rooted in the legacy of Abraham's progeny.

As for the Palestinians, accusations of genocide against Israel fail to align with demographic realities. In fact, since Israel's complete withdrawal from Gaza in 2005 and the handover of control to the Palestinian Authority, the region's population has seen a substantial increase. United Nations data indicate that Gaza's population grew from 450,000 to 780,000 during that period, marking a 73% rise.

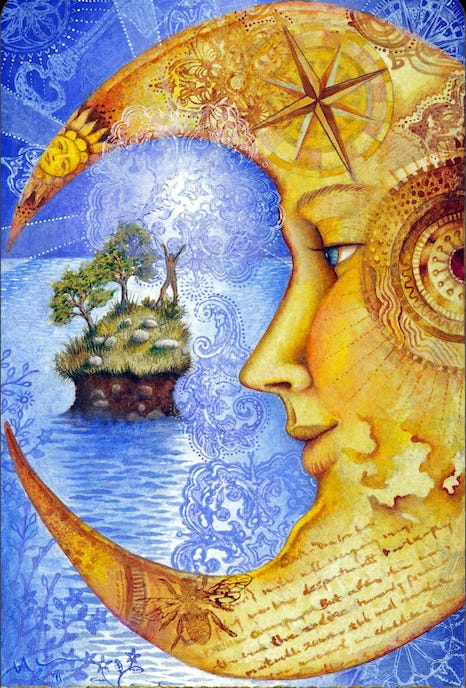

In conclusion, I should like to revisit the banner Moon visual with its eight-pointed star — the Star of Ishtar from the Mesopotamian civilization —underscoring its enduring symbolic significance.

This ancient symbol, representing the goddess Ishtar, encompasses themes of fertility, love, war and power, seamlessly blending aspects of life and divinity that resonate across cultures and epochs. The duality of Ishtar, embodying both nurturing and warfare, reflects the intricate nature of human society — a mosaic of creation and destruction, love and conflict.

The eight-pointed star, resplendent beside the moon, stands as a testament to the lasting impact of ancient symbols and myths in our collective consciousness. It underscores the significant role that celestial bodies and mythological figures play in our ongoing journey to understand our place in the universe.

In the Monastery of the Mind, as we contemplate this symbol from Mesopotamian civilization, we discover a connection not only to our past but also to the everlasting essence of the human condition.

This imagery transports us to an era when the stars and the moon transcended their roles as mere celestial bodies, becoming integral to the narrative of human existence. The image transcends mere representation; it becomes a dialogue across millennia, echoing the perennial human quest to find meaning both in the cosmos and within our own being.

We shall return to this feminine symbolism in later articles as we detail apparitions of Mary, the mother of Jesus, that soon will become of great interest worldwide amidst 2024’s turmoil and strife. We will primarily focus on the continuing apparitions of Mary at the tiny hamlet of Medugorje in the former Yugoslavia, where I once lived.

Monasteries of the Mind (article)